Every once in a while, the Kurram district, located near the Afghan border in Pakistan’s northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), is marred by violence and bloodshed. These recurring episodes of horrific carnages continue to claim the lives of dozens of people across the conflict-ridden parts of the district, primarily due to various land disputes which, when fuelled by tribal vengeance, escalate into sectarian tensions affecting the local population residing in the upper, central, and lower tehsils of Kurram.

The locals recall that the district, also tainted by militancy, was once a pluralistic society where people stood by each other through storms and happy moments. However, deeply embedded differences have overshadowed the camaraderie of its people, with devastating consequences.

The latest spate of violence began late July but intensified after the November 21 gun attack on a convoy of 200 passenger vehicles travelling through the district’s remote area taking the Thall-Parachinar Road. At least 52 people were killed in the incident that triggered a series of retaliatory attacks taking the death toll to 133 which included the injured that gradually succumbed to their injuries. The brutal exchange of violence, which lasted six days, cost the blood of innocents. Both the Sunni and Shia communities mourned the loss of their loved ones with no one to turn to for justice as vengeance took over sanity in one of Pakistan’s most scenic valleys located across the Durand Line’s tribal belt.

The most recent clashes entail a conflict between a Shia-majority tribe, Maleekhel, and a Sunni-majority tribe, Madgi Kalay, over a large area of agricultural land owned by the Shia tribe in the Boshehra village, which is located 15 kilometres from the south of the Parachinar town. In an interview to Al Jazeera, a local peace committee member said that the land was leased to the Sunni tribe for farming and the lease was to end in July this year. The clashes began when the Madgi Kalay tribe refused to return the land.

The killings and the dispute, halted at the moment following a ceasefire agreement, are not as simple as one may believe it to be. Violence, in this region, has been addressed by government’s intervention time and again but short-lived peace and calm largely occur following consensus of tribal elders during jirga, a tribal council meeting. Geo.tv explores the deadly impact of the ongoing conflict on the district and its populace, the history of the region’s tribal and sectarian dynamics, as well as the wreckage of war on terror with insight from the people of Kurram, its local authorities, provincial government and regional experts.

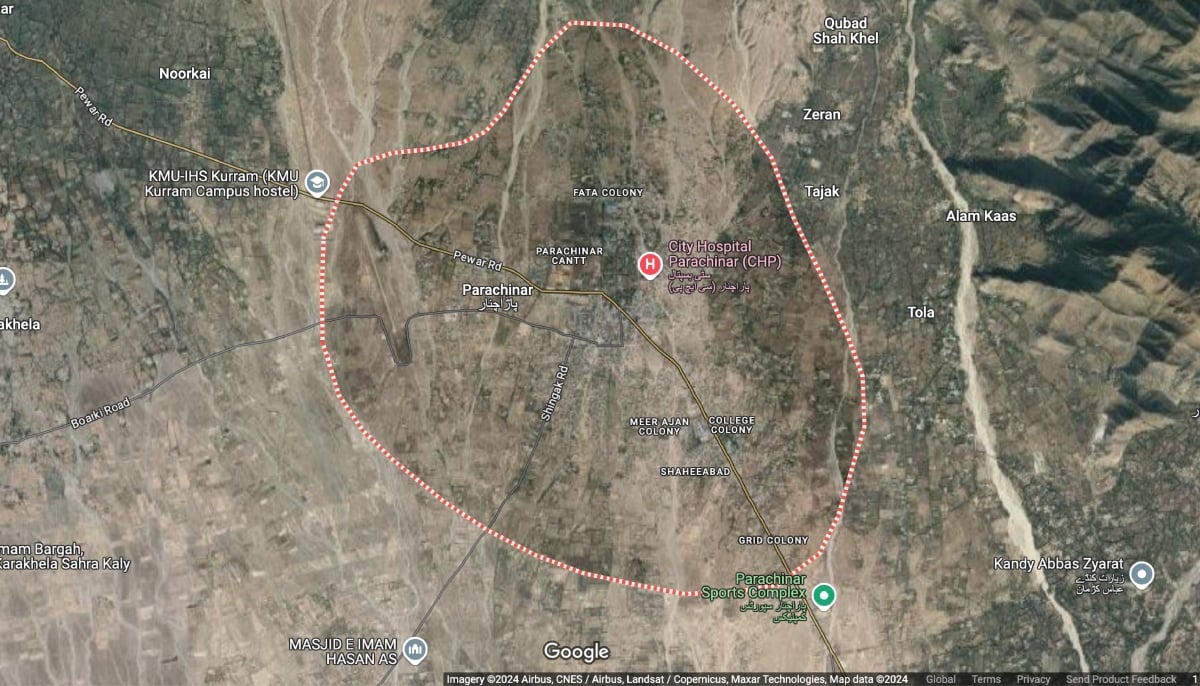

No end to suffering as Parachinar, adjoining villages remain disconnected

Each time when clashes break out in Kurram, it is the locals that suffer the most, particularly those in Parachinar, as the town remains disconnected due to closure of the main road for over 70 days. Currently, contact with the town is limited to air routes, as both the Thall-Parachinar Road and the Afghan border remain shut for an extended period.

Days after the recent deadly clashes, the residents of the town located in Upper Kurram saw depleting essential commodities including edibles, medicines and fuel. At least 29 children and several other patients, according to a The News report, have died due to scarcity of medicines and unavailability of surgical services since October 1, indicating an imminent healthcare crisis. The provincial government, however, continues to reject these claims.

Children are dying from pneumonia and preventable diseases, while patients endure unimaginable pain due to the unavailability of life-saving treatments. — Riaz Turi

District Headquarters (DHQ) Hospital Parachinar Medical Superintendent Dr Syed Mir Hassan Jan, in a statement, said that the Health Directorate Peshawar has sent a stock of medicines, but it is not sufficient to meet the hospital’s requirements.

Riaz Ali Turi, a political activist from Parachinar, told Geo.tv that the isolation had led to critical shortages of food and the complete depletion of essential medicines.

“Children are dying from pneumonia and preventable diseases, while patients endure unimaginable pain due to the unavailability of life-saving treatments,” he said, terming the situation as a “huge humanitarian crisis”.

Turi, addressing the federal and provincial governments, as well as, humanitarian organisations, requested intervention in ensuring the provision of medicines to DHQ Hospital Parachinar. “Every moment of inaction costs lives. It is time to let humanity prevail,” said Turi, adding that the suffering of the town — housing more than 800,000 people — should be a matter of grave concern for the government of Pakistan.

He lamented the communication and commute issues that people in Parachinar are facing. Parachinar residents visiting other parts of the country, he said, are now waiting to go back to their hometown, as they can no longer afford to live elsewhere.

In conversation with Geo.tv, Ishtiaque Hussain — a 29-year-old resident of Parachinar — also expressed deep concern over the lack of basic commodities in Parachinar, revealing that it is going to be two months since no essential commodities have been brought in the town.

Hussain also described that women from both sects were also affected by the recent conflict. Some pregnant women from the Bagzai village, located near Bagan and comprising Sunni population, passed away due to lack of facilities for safe delivery. Those injured following the clashes, he added, are also not receiving proper medical facilities due to lack of doctors and medicines. While residents with serious diseases such as cardiac issues, cancer, diabetes, and others illnesses, are unable to get prescribed medicines.

The temporary but complete internet shutdown for more than a week also disconnected the mountainous town from the rest of the world.

“My own work was impacted,” Hussain continued — who is also a SEO expert — due to the clashes and the closure of the internet in the region from November 23 to December 6.

Meanwhile, educational institutions were shut down impacting the education of schoolchildren, while university students who were supposed to appear for exams and admission interviews in other parts of the country remained restricted in the town due to security reasons.

The lack of fuel in the town is also an urgent issue impacting the mobility of residents.

Meanwhile, Imran Muqbal — a social activist and local politician from Upper Kurram — told Geo.tv that while Parachinar is receiving aid and items via helicopter by the provincial government, there are extreme suffering in small village councils which still remain deprived. “Neither rescue teams nor government representatives have visited these villages.”

While talking to Geo.tv, Deputy Commissioner Kurram Javedullah Mehsud acknowledged the continuous closure of the road to Parachinar due to which medicines and other items were being transported via helicopter. He said that the provincial government shifted some injured people to Peshawar through the helicopter two weeks ago. DC Mehsud admitted that there is a shortage of fuel as the region’s population is massive and the demand is more than the supply.

Barrister Mohammad Ali Saif, the adviser to the KP chief minister on information, on December 18, said that the main highway in the district would only reopen after armed groups surrender heavy weapons to the government.

“Tribal leaders have been urged to take responsibility for this issue and support the government in the process of surrendering weapons to ensure a sustainable resolution of the crisis,” said Saif, addressing a presser in Peshawar.

According to The News, deadlock in negotiations between the warring tribes in the district continues as one group has refused to surrender its weapons.

How locals and experts view conflict in Kurram

As the years-old conflict continues till date, the locals of Kurram — representing the two Muslim sects — share their views about its tribal, sectarian and political dynamics, while holding successive Pakistani governments accountable for not being able to play an effective role to bring an end to it.

Hussain, the Parachinar resident, described the situation around the conflict “really fragile”. He termed the ceasefire as a “mere break”, claiming that another clash might potentially take place soon. Denouncing the role of the local government in the ongoing clashes, he said: “They acted as brokers for exchange of dead bodies during a period of ceasefire. They have done nothing else.”

Whenever there is a ceasefire, it is only for a month or a couple of weeks. — Imran Muqbal

Locals of the district also cite the significance of the 2008 Murree Accord, also known as Murree Jirga (jirga means tribal council). The agreement, which was finalised between the two sectarian groups in Kurram, remains crucial to the dispute’s resolution. According to an article published by the CARC Research in Social Sciences, this accordinvolved 15 council elders each from both sides of the warring groups — Sunni Bangash and Shia Turi tribes, making it a significant agreement to resolve future disputes initiated for peace in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) district.

The two tribes, on October 15, 2008, signed a permanent peace agreement to avoid sect-based disputes during their meeting held in Murree. The pact also included 23 members from a reconciliatory delegation.

“All the members of the accord agreed on the smooth implementation without any further delay for the peaceful coexistence and peace building. The jirga concluded with the final verdict that if any of the two groups would violate any the provision of the 2008 Accord he or they be paid Rs60 million as fine of violating the jirga,” the article mentioned, further stating that the landmark agreement “achieved major success in bringing stability and peace in way of peace building among the two warring groups”.

However, the benefit of the agreement in Kurram’s current dynamics are barely visible.

Muqbal lamented the lack of implementation of the Murree agreement, which was “acceptable” to both sects and criticised the role of the local government as well as the inability of LEAs in ensuring sustainable peace in the district.

“They are unable to get deals implemented or arrest terrorists. Whenever there is a ceasefire, it is only for a month or a couple of weeks.”

The social activist recalled that the sectarian conflict in Kurram intensified in 2007 and termed the recent wave of clashes between the tribes as the “deadliest” in Kurram’s history. He added that even women and their dignity were not spared during the recent conflict.

Turi, when commenting on the land disputes in the district, told Geo.tv that this is the only tribal belt in the history of KP, and even Pakistan, where the compiled revenue record is available since the British era.

He also highlighted that government’s negligence is a huge factor contributing to the unresolved state of the issue.

“Since the 1960s, some areas remain strongly disputed between Shia and Sunni tribes. However, these small disputes were not difficult for the governments to settle but they just kept establishing high-level commissions that took months to compile reports and take decisions that were never implemented.”

Turi added that unrest in Afghanistan remained another factor, as the terrorist outfits there have several times targeted the members of the Shia sect. He also mentioned a third factor: the lack of the government’s writ in the region where militant elements exist and are trying to regain power. “It is easy for them to fuel the fire in a restive region rather than control those which are relatively peaceful.”

Had the government taken interest and if its jirga was serious, the deadly clashes would not have taken place. — Nabi Jan Orakzai

Earlier, Turi said, conflicts have always existed in the region but elders of both communities would always come forward to resolve them throigh consensus, but what is happening now are “deeply-rooted acts of hate and barbarism”.

Nabi Jan Orakzai, a local journalist from Kurram who now resides in Peshawar, also fears that the recent clashes will have “dangerous consequences” in the region.

Since the issue began with a land dispute decades ago, he added, it was not difficult for the government or a jirga to resolve it. But now, a once territorial dispute has turned into a sectarian matter. “Had the government taken interest and if its jirga was serious, the deadly clashes would not have taken place.”

Dr Irfan Ashraf, an academic teaching at the University of Peshawar, said that after the merger of the districts, it was the responsibility of the state to establish institutions and increase its intervention in the region through police, judiciary and others.

“Therefore, even the most trivial issue turns massive that leads to revenge and bloodshed. However, all of it is basically linked to the state’s policy,” said Ashraf.

How local and provincial governments are handling Kurram conflict?

The local Kurram government and the KP administration, with help from local elders of both communities, have brokered a ceasefire deal between the tribes that made it possible for peace to prevail in the valley — only until a potential looming clash rears its head again.

The recent surge of clashes saw a high-level Grand Peace Jirga, facilitated by KP, attempt to resolve the ongoing crisis in the district. The jirga, attended by over 100 people including the elders of the region’s rival tribes, was chaired by Kohat Division Commissioner Syed Motasim Billah Shah, following which important decisions were taken to restore peace in the district comprising an agreement of a ceasefire.

In our strategy for peace in the region, we are establishing security pickets from Thall to Tari Mangal alongside close circuit television (CCTV) cameras. — Barrister Muhammad Ali Khan Saif

However, these efforts have failed in bringing the warring tribes to a consensus as negotiations have now been continuing for weeks. As the peace efforts began in the district earlier in December, a local social activist and member of the Bagan Committee from Lower Kurram, was shot dead by unidentified gunmen after attending the meeting.

When asked what steps the KP government has taken to ensure long-term peace between the warring tribes, Barrister Saif claimed the it took immediate measures in response to these escalations.

“I personally led a delegation to mediate and secure a ceasefire, ensure the safe return of the deceased, and facilitate the release of prisoners from both sides,” said the minister, highlighting that KP’s plan to re-establishing the jirga was essential for long-term peace, as it provided a platform for meaningful dialogue.

Another significant issue, according to Barrister Saif, is the establishment of reinforced bunkers along the main road by both groups which have made the primary route between areas insecure, as fighters from both sides are deployed in these positions during periods of conflict. He added that KP Chief Minister Ali Amin Gandapur, for the first time, has ordered that these bunkers be dismantled, and both groups have agreed to cooperate in the process.

The minister maintained it is crucial to recognise the unique challenges of operating in these tribal areas. “Law enforcement cannot function in the same manner as in settled areas due to the complex social, cultural, and political dynamics,” said Barrister Saif, indicating care and inclusivity in the government’s approach by making all stakeholders a part of the decision-making process.

Responding to a question about the safety of passengers travelling through the Thall-Parachinar or Parachinar-Peshawar Highway, he said that CM Gandapur has ordered the repair and construction of alternative routes to facilitate the safe and easy mobility of local residents.

However, he confirmed that currently, the Thall-Parachinar or Parachinar-Peshawar Highway is the only means of travel for people moving between Parachinar and other parts of the province.

On the other hand, Kurram Deputy Commissioner Javedullah Mehsud spoke about the significance of village committees in the region in the past and at the time, he said, the government was also grappling with militancy from Afghanistan in Central Kurram.

“In our strategy for peace in the region, we are establishing security pickets from Thall to Tari Mangal alongside close circuit television (CCTV) cameras,” he said, adding that other steps will also be taken to ensure a sustainable atmosphere in the region.

Tracing history of land dispute, sectarian violence and terrorism in Kurram

To understand the root cause of violence in Kurram, it is crucial to know why the issue is largely linked to an unresolved land settlement and distribution dispute. The geographical positioning of Kurram, which spans across 3,380 square kilometres of area and houses a population of approximately 700,000 people of which 42% are Shias, plays a significant role. The district, which was part of the former central Fata before the merger of tribal areas in May 2018, is bordered in the North and West by Afghanistan, closer to Kabul and other parts of the country.

Mariam Abou Zahab — a late French academic, political scientist and sociologist with expertise in the politics of Pakistan and Afghanistan — wrote that the disputes between the two major sectarian groups encompass land, hills, water and forests. The occasional incidents of communal violence, according to Abou Zahab, took place since the 1930s during religious occasions such as the first Islamic month of Muharram and Nowruz (the Iranian new year) — years before Partition in 1947.

In her writing, she stated that the Turis, who were under the domination of the Bangash until the 18th century, formed the largest tribe in Kurram and possessed the most fertile land. The years of conflict in the region reflect the underlying economic and territorial grievances, which remain interconnected with land disputes and sectarian tension only intensifying till date. Following a conflict, in retribution for an insult to a Turi woman, the Bangash were pushed towards Lower Kurram, Abou Zahab noted. During the British era, the Turis — who paid revenues for the land to the Afghan state since the 1850s — requested the British to assume control of the former Kurram Agency’s administration with headquarters to be located in Parachinar, as they feared aggression from the Sunni tribes.

The growing sectarian conflict in the region before Pakistan came into being, also dates back to the 1938 clashes in Lucknow, where the Kurram tribesmen travelled to offer support to their respective sects. Their journey, however, was hindered by rival groups — laying the ground for the continuing sectarian differences in the region. In 1961, a religious procession saw clashes erupting in Sadda, an area in Lower Kurram.

The Iranian revolution in the 1970s and the arrival of Afghan refugees, largely Sunnis, in Pakistan during the 1980s following the Soviet invasion triggered a massive transformation in the region’s demographic. With modern weaponry easily available, the frequency of clashes between the two sectarian communities grew and intensified simultaneously. “The first large-scale attack took place in 1986 when the Turis prevented Sunni mujahideen from passing through to Afghanistan,” wrote the French political scientist, highlighting the era of former military ruler General Zia ul-Haq.

Major clashes also occurred in 1996 that led to the killing of people from both sects. While tribal jirgas and efforts of communal harmony by elders minimised differences in the past, most experts claim it was the conflict in April 2007 that led to an increase in distance between the two communities — a time when the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) still terrorised the region. The issue was exacerbated in November of the same year when Waziristan’s Taliban under the command of Hakeemullah Mehsud — a TTP leader killed by a United States drone strike in November 2013 — from Orakzai led a new spell of violence in the region, which escalated to the summer of 2008. An upsurge was also documented in the wake of violence in 2009 and the years ahead.

Violence also grew after the emergence of the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) in January 2015, which — according to the Center of Strategic and International Studies — came into being following the defection of the local Taliban. The 2017 suicide attacks in Parachinar targeted locals, which deepened the geographical divide between the two sects.

It is also crucial to note the presence of fighter groups in the region such as the Zainabiyoun Brigade — an armed group banned by Pakistan — which came into being with the aim of fighting in Syria’s Civil War to support the now-ousted Syrian ruler Bashar al-Assad. The presence of the group is acknowledged by local youth and tribal elders stating that the men would go from Parachinar to “fight Daesh”.

The Thall-Parachinar Road holds immense significance with regard to the security of convoys travelling through the region, as certain areas along this route remain vulnerable to attacks. Since the 1980s in Kurram, however, several tribesmen, as described by Abou Zahab, have been killed over varying long-standing disputes.

What is the solution?

The long-standing disputes of the district warrant a sustainable solution that not only protects the lives of people but also guarantees peace for the future. The imposition of indefinite ceasefires, as per experts, has not been viable for the local population as they often include the closure of roads that impact the everyday life of the locals. It is, however, important to understand how a conflict as complex as one in Kurram will be resolved and what role the local and provincial governments as well as other regional stakeholders play in ensuring lasting peace in the district.

The Grand Jirga remains actively engaged with both parties in District Kurram to ensure a path toward permanent peace. — Barrister Muhammad Ali Khan Saif

Barrister Saif said that the provincial government is optimistic about the resolution of the ongoing issues and believes that they can be resolved amicably. During the meeting of the Grand Jirga and the peace committee in Kohat, it was decided that no protests would be allowed on the Thall-Kohat Road, and in the event of non-compliance, the police would take necessary action against those responsible.

“The Grand Jirga remains actively engaged with both parties in District Kurram to ensure a path toward permanent peace, emphasising the need for collaboration, mutual respect, and an enduring solution for all stakeholders,” he said.

Deweaponisation, according to Muqbal, is the “only lasting solution” to this issue.

“There should be deweaponisation in the district and the conduct of an operation against terrorist organisations in Upper and Central Kurram just like it was done against Talibanisation in the past in Lower Kurram,” he said, sharing what could possibly resolve the recurring issue.

He also suggested the establishment of security checkposts in the district to protect the population. “It will be difficult to contain this fire if the dangerous areas of the district are not declared a red zone.”

Ashraf, sharing his views on ensuring long-term solutions, termed the jirga of the people as a way to resolve the issues. The authority of which, he added, lies with the communities’ elders, the people or parliament.

“If the state is sincere, it should stand with them, as these are the same people who have been oppressed. There won’t be long-term peace in the region if the state does not take their consent,” he stated.

Commenting on finding a lasting solution to the issue, Turi maintained that the issue can be resolved if there is a will to find a solution. He also suggested the constitution of a high-level commission with representation from the federal and provincial governments as well as local Shia and Sunni.

“They should announce that the commission will implement its decisions by hook or by crook,” concluded Turi.

Rabia Mushtaq is a staffer at Geo.tv. She posts on X @rabiamush

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv